[Revision: July 25, 2015]

Table Of Contents

-

A. INTRODUCTION

B. THE OPENING: TAOIST METAPHYSICS IN THE EAST WIND

C. MR. BANKS LIFE OF PRECISION

D. THE WU-WEI OF CLEANING THE NURSERY

E. PLAYING WITH INDETERMINANT WORDS ON A JOLLY HOLIDAY

F. THE BALANCE IN UNCLE ALBERT

G. DIRECTED SYNCHRONICITY AT THE FIDUCIARY BANK

H. THE TRIP TO SEE THE GATEWAY OF CREATION OVER THE ROOFTOPS OF LONDON

I. MARY POPPINS FOLLOWS TAO AND LEAVES WITHOUT SAYING GOODBYE

Of all the English-language films I’ve ever seen, only one stands out as an embodiment of a classical Taoist world from beginning to end: Disney’s Mary Poppins. From the opening scene, when jack-of-all-trades Bert, singing and dancing as a one-man band, senses a change in the wind that heralds the coming of the airborne nanny, to the end when Admiral Boom barks that the wind has reversed course and she takes off for unknown parts, the 1964 Disney movie (not the books by Pamela Travers, not the stage musical) is the story of a Taoist messiah, come to help smooth the domestic storm brewing in the home at 17 Cherry Tree Lane, resetting not only that household but the process, the Bank of England too, which could be viewed as a doorway to the country and the world.

On its surface, Mary Poppins is a children’s film, with a family-affirming ethic, but a Taoist “going with the flow” philosophy underlies it’s free and easy fun and adventures. Her nanny teaches the practice of wu-wei, the importance of a balanced life, to revel in the spontaneous moment. To size up Mary Poppins as merely philosophically Taoist would be to miss the big picture: the script and the visuals describe a fully-realized Taoist universe with all its mysticism intact. The Disney rendition hews more faithfully to the main texts of classical Taoism than more recent “religious” movies like “The Matrix” which explicitly reference Eastern religions. The question is whether there is support for such a reading as more than an imaginative conjuring.

Although filmed more than 50 years ago, it remains, despite the continued rise of Eastern religions in filmed entertainment, without peer as a Taoism primer, and illustrates in vivid color, actions and words, the major Taoist precepts. Walt Disney certainly did not intend to make a movie about Taoism, set in of all places Edwardian England. He was theologically and philosophically a Christian (“All I ask of myself: ‘Live a good Christian life’.”), who believed that “deeds, rather words, express my concept of the part religion should play in everyday life.” (Pinsky, Mark, The Gospel According To Disney, Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, c. 2004, p. 20.) However, many of his movies paid respect to multicultural traditions, assembled of “images and sequences with implications and messages – inspirational and disturbing, subtle and strong, scientific and pagan and Christian….” (Pinsky, Gospel According To Disney, p. 33.)

When Mary Poppins was being adapted from the books and filmed, the New Age and Counterculture streams had already ferried eastern thought widely into American consciousness. (See, e.g., Groothuis, Douglas, Unmasking The New Age, Downers Grove: Varsity Press, c. 1986, pp. 37-38.) Pamela Travers (the author of the Mary Poppins book series) herself was a New Age spiritualist, a devotee of the spiritual leader George Gurdjieff and the Theosophists, and read and researched extensively the religions and philosophies of the East. (See, e.g., Lawson, Valerie, Mary Poppins She Wrote, New York: Simon Schuster, c. 1999, pp. 121.)

When asked whether Mary Poppins “teaching — if one can call it that — resemble that of Christ in his parables,” Travers replied “My Zen master, because I’ve studied Zen for a long time, told me that every one (and all the stories weren’t written then) of the Mary Poppins stories is in essence a Zen story.” Zen, of course, is a joining Buddhism and Taoism. (See, e.g., Lawson, Mary Poppins She Wrote, p. 4.) It must be noted that Travers hated the movie, but that the agreement between her and Disney gave her script approval rights. (Lawson, Mary Poppins She Wrote, p. 239.)

The script scribes and Walt Disney himself (who supervised and contributed to the creative process) could construct a Taoist tale from the elements in the books and from the rhetoric in the culture around them. For example, the whole Uncle Albert sequence – very important to a Taoist interpretation of Mary Poppins – was Walt’s idea. (Stein, Ruthe, Tony Walton talks about ‘Mary Poppins’ costumes, San Francisco Chronicle, Mar. 18, 2011). People have interpreted Disney’s Mary Poppins from other points of view (the books have been mistaken for Satanic, for example), but it’s remarkable that a Taoist reading from beginning to end is possible given that Taoism is still poorly understood today, never mind the 1960s. (See, e.g., Kohn, Livia, Daoism Handbook, Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, c. 2000, p. xi.) Even the “Feed The Birds” sequence, which at first seems more Christian or Buddhist in its exhortation to compassion and charity, conceals a Taoist bent because of its hidden motive. I won’t relay the complete story or plot here.

Below are my takes on a Taoist interpretation of a few images and scenes from Mary Poppins. The main sources for this analysis are the philosophy and theology in the three classic texts of Taoism: Tao Te Ching (道德經), The Book Of Chuang Tzu (莊子) and The Book Of Lieh Tzu (列子).

B. THE OPENING: TAOIST METAPHYSICS IN THE EAST WIND

The movie opens with the character Bert in the park performing as a one-man band, when suddenly, the wind changes direction. He stops performing and in a musical aside, ruminates on the weather. Although he can’t quite pinpoint what is coming, he does have the feeling that whatever it is, it “all happened before”, establishing the cyclical nature of the unfolding story.

- Wind’s in the east

There’s mist coming in

Like something is brewing, about to begin

Tao is the name for the mystical cosmic mother and the universe within. In Taoism, all things are made of solidified energy (氣 pronounced qi or chi) and are surrounded by fluidic or vaporous energy in the form of air, moisture or gas. The vacuum of outer space is filled with invisible chi energy. (See, e.g., TaoTeChing ch. 42.) Taoist imagery references the movement and attributes of water as a representation of the energy currents within Tao and of Tao itself. On dry land, however, wind replaces water as the main representation of the Great Flow. The Taoist art of Feng-Shui – a kind of geomancy – redirects energy flows in living spaces through interior design or landscaping. Feng-Shui (風水) means “wind water”. In Taoist alchemical symbolism, atmospheric mist which hovers between heaven and earth is said to be the chi or “vapor of Tao”. (Wong, Eva, The Shambhala Guide To Taoism, Boston: Shambhala, c. 1997, p. 220.)

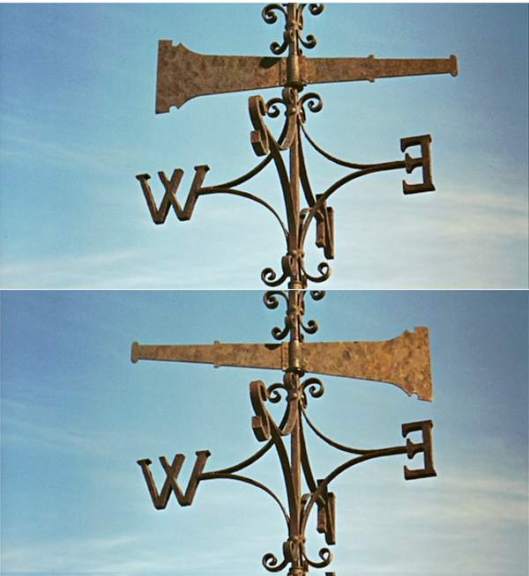

This lyric foreshadows the arrival of Mary Poppins as someone associated with the wind. In the Book Of Chuang Tzu, the Taoist Sage Lieh Tzu also rides the physical wind carry him great distances, but aspires to riding the breaths of change to be free of the effects of fate. (ChuangTzu ch. 1; Watson, The Complete Works Of Chuang Tzu, p. 32.) Mary Poppins rides the physical wind and the winds of change. Hence, she too hovers above fate, but simultaneously lives harmoniously with change. A weather vane points to the east before she arrives. It swings around to the west before she leaves. She follows the wind (follows the currents of Tao). When the children ask her if she’ll stay with them forever, she replies: “I shall stay until the wind changes,” to herald and accustom them to unsettling change.

C. MR. BANKS LIFE OF PRECISION

The Tao follows the way of spontaneity (自然 or zi ran), meaning that like a natural watercourse, it can change direction unexpectedly, even going backward. (See TaoTeChing chs. 25, 41, Lau.) Mary Poppins follows the way of spontaneity, because she travels with the wind.

In the song “The Life I Lead”, George Banks, the patriarch of the Banks Family at 17 Cherry Tree Lane, reflects on the joys of being a well-to-do Englishman in 1910 (Edwardian period). It is a life of precision and consistency, because he follows a set schedule. When he discovers that the nanny of his 2 children has quit because she’s “had her fill” of their raucous behavior, he explains the need for a nanny who’s a “general” to discipline the children and enforce strict behavior:

- I run my home precisely on schedule

At 6:01, I march through my door

My slippers, sherry, and pipe are due at 6:02

Consistent is the life I lead!

….

A British bank is run with precision

A British home requires nothing less!

Tradition, discipline, and rules must be the tools

Without them – disorder! Catastrophe! Anarchy!

This scene continues the foreshadowing of Mary Poppins and subtly paints her as being like a Taoist. As Bert announced earlier, the wind is in the east at Cherry Tree Lane and here is associated with illness. In Taoist metaphysics, the world is like a living body and if the energy coursing through it is an ill wind, then the body is sick. Admiral Boom remarks “Storm signals are up at 17. Heavy weather brewing there.” The heavy weather includes yelling and screaming and the sounds of objects breaking.

Mary Poppins arrives to heal the disharmony at no. 17, because she descends on the east wind. The subject of illness is raised again. During the interview, he becomes confused when he discovers that Mary Poppins is holding the copy of the children’s ad for a sweet nanny, which he had torn up. She asks him if he’s ill and suggests a trial period. The nanny he will hire will be an anarchist, exactly the type of nanny he does not want. Her lessons and activities for the children will seem to defy convention and tradition, just as the children will seem to defy discipline and rules.

Classical Taoism philosophy is one of the earliest forms of anarchic philosophy, but almost paradoxically, does not regard the State (or the Bank of England – which subtly operates as state authority in the story) as unnatural. These institutions both actual and socially constructed (like the Bank and the Banks family) are natural institutions, part of the landscape of the myriad things. (Ames, Roger, The Art Of Rulership, Albany: SUNY Press, c. 1994, p. 113.) However, there are characters who function outside these institutions, like Bert and Mary Poppins herself, who interact with these institutions but seem not to buy into them. They function more like engineers, to assist in reorganization as necessary.

D. THE WU-WEI OF CLEANING THE NURSERY

A complementary principle to zi-ran spontaneity is wu-wei (無爲) inaction. Wu-wei means “without action” or action that is without intentional conscious effort. A person is perfectly spontaneous if there is no thought or intention or hesitation to interfere with one’s natural inclinations. However, neither is wu-wei justification for indulging every whim and desire. Spontaneous action follows Tao and inborn nature and does not polarize. Wu-wei is almost absent-minded action that seems to complete without the person even being aware of it. Yet, it is subconsicous awareness that can prevent disaster, if inaction results in danger. Effortless, spontaneous wu-wei arises from the interaction of one’s inborn nature (生 sheng), which is an integral part of one’s soul (德 Te or Virtue) in harmony with Tao and Tao currents.

The “Spoonful Of Sugar” sequence demonstrates a special-effects version of effortless wu-wei. After Mary Poppins meets the children, she tells them it’s time to tidy up the nursery. The children regard her suspiciously because she was supposed to be a nanny who “plays games, all sorts”, not put them to work. She replies that it could be a game, depending on their point of view and sings the song “A Spoonful Of Sugar”:

- In every job that must be done

There is an element of fun

You find the fun and snap!

The job’s a game….

The job really is a “snap”. She snaps her fingers and the clothes seem to put themselves away, the bed seems to make itself. In the picture below, one of the children, Jane, snaps her fingers and the toy soldiers come to life and march into the toy box. She only stands there and watches (witnesses) them.

In a real world example of wu-wei, someone may start a task, drift off in unrelated thoughts or daydreams while working, and when their attention comes back, the job is all done, seemingly without any memory of having done it. The body actually does the work, but the mind detaches and maintains just enough awareness to witness the action. The “Spoonful Of Sugar” sequence is the most basic form of effortless wu-wei.

In classical Taoism, the principle of wu-wei expands well beyond the performance of drudge and toil to challenge the notion of human agency and makes implications about the nature of the cosmos. The two classical attributes of wu-wei are: effortless, non-intentional action and non-interference. Non-interference is a term more applicable to interaction with other people, similar to the concept of laissez-faire.

“The Master does nothing, yet he leaves nothing undone.” (TTC ch. 38; Osho, Tao Te Ching, San Antonio: MSAC Philosophy Grp, c. 2008, p. 38. See also Wang, Keping, The Classic Of The Dao: A New Investigation, Beijing: Foreign Language Press, c. 1998, pp. 217-8). The ChuangTzu chapter 6 explores the question of human agency. Free will depends on the presence of an absolute reference with which to compare action. However, a Taoist universe constantly transforms, and there is no fixed reference.

- Knowing depends on something with which it has to be plumb; the trouble is that what it depends on is never fixed. How do I know that he doer I call ‘Heaven’ is not the man? How do I know that the doer I call the ‘man’ is not Heaven?

- Graham, Angus C., Chuang Tzu – The Inner Chapters, London: George Allen & Unwin, c. 1981, p. 84.

E. PLAYING WITH INDETERMINANT WORDS ON A JOLLY HOLIDAY

The first chapter of the TaoTeChing lays the groundwork for a distrust in language that pervades the classical Taoist texts. The name “Tao” is a symbol for the cosmic entity, but the name is misleading. Tao enwombs the universe but is itself nothingness (wu 無). Yet in Taoism, things do arise from nothingness, just as in an earlier scene in the movie, things seem to materialize out of Mary Poppins empty carpet bag. Individual things in Tao have true names (different from given names). Tao is totality. In Taoist naming theory, all things have a unique name, because the cosmic mother holds a “prototype” for each thing, its soul, called Virtue or Te (德). When a thing is born or comes into existence, it obtains its Te from Tao. Because Tao is the repository of the Te of all things, Tao is complete and cannot have a true name.

- The Tao that can be spoken is not the eternal Tao

The name that can be named is not the eternal name….

- Lin, Derek, Tao Te Ching, Woodstock: Skylight Paths, c. 2006, ch. 1.

The Book of Chuang Tzu takes especial pleasure and cleverness in juggling with the indeterminacy of language. A story in chapter 2 called “The Happiness Of Fish”, for example, hurls flutters of words against logic. In that same chapter, however, a story called “The Hinge Of Tao” argues that the mistrust of words may be resolved, by understanding that the ambiguity in words brings all things to unity, to the realization that all things are within and belong to Tao.

- Words have something to say. But if what they have to say is not fixed, then do they really say something? … What do words rely upon, that we have right and wrong?… When the Way relies on little accomplishments and words rely on vain show, then we have the rights and wrongs of the Confucians and the Mo-ists. What one calls right the other calls wrong; what one calls wrong the other calls right. But if we want to right their wrongs and wrong their rights, then the best thing to use is clarity.

….

A state in which “this” and “that” no longer find their opposites is called the hinge of the Way. When the hinge is fitted into the socket, it can respond endlessly. Its right then is a single endlessness and its wrong too is a single endlessness. So, I say, the best thing to use is clarity.

- Watson, Burton, The Complete Works Of Chuang Tzu, New York: Columbia University Press, c. 1968, pp. 39-40.

In the picture above, Mary, Bert and the children have jumped inside one of Bert’s chalk pavement drawings of an English countryside. They ride a merry-go-round. The horses hop free of the carousel and enter a race track in time to compete in a race. When Mary wins the race, a news reporters says to her “There probably aren’t words to describe your emotions.” She replies “On the contrary, there’s a very good word” and launches into the song “Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious”.

- Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious!

Even though the sound of it something quite atrocious

If you say it loud enough you’ll always sound precocious

…

He travelled all around the world And everywhere he went

He’d use his word and all would say “There goes a clever gent”

When Dukes and Maharajahs pass the time of day with me

I’d say me special word and then they ask me out to tea

…..

Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious is a uniquely made-up word, made up for the movie only – it does not appear in the books. Mary Poppins uses it to describe an indescribable emotion. Bert uses it as indication of a proper education, to impress people. It seems to have different meanings and different uses. In that sense, supercalifragilissticexpialidocious is a mystical word for totality and in that sense, it could even represent Tao.

Supercalifragilissticexpialidocious conveys equally moral ambiguity, as it does definitional ambiguity. The word sounds “atrocious” but if said forcefully seems “precocious”. As a child, Bert is “bad” for not speaking, but is good for speaking nonsense. Everywhere he goes, they assume he’ a “clever gent” when the only visible cleverness he shows is uttering the word. Finally, its a word of transformation, because “it can change your life”.

In the story called the Hinge of Tao, the power of and ambiguity in language to transform transcribes a circle. “Its right then is a single endlessness and its wrong too is a single endlessness.” A hinge spins on its pivot 360 degrees, but each degree can be divided into infinite positions. Hence, there is a potential for all things and all things are within Tao, so the diverse world is the natural world. A Taoist who can pivot like a hinge in response to the world (by seeing all things as one) can react with the spontaneity of Tao. The last stanza of the song Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious is about flexibly and reflexively responding to all situations that present in the world:

- So when the cat has got your tongue

There’s no need for dismay

Just summon up this word and you’ve got a lot to say….

Which is to say that the word sercalifragilissticexpialidocious means nothing and everything at the same time, and so fits all occasions.

F. THE BALANCE IN UNCLE ALBERT

- Who can be muddy and yet, settling, slowly become limpid?

Who can be at rest and yet, stirring, slowly come to life?

He who holds fast to this way

Desires not to be full.

It is because he is not full

That he can be worn and yet newly made.

- TTC ch. 15; Lau, D.C., Tao Te Ching, London: Penguin Books, c. 1963, p. 15.

A Taoist lives a balanced life and avoids polarization. To polarize is to go overboard and sustain damage. In the quote above from the TaoTeChing ch. 15, muddiness and limpidness are two states of living, one active and one at rest. To polarize (to be full) means to be limpid or muddy all the time. One who is always muddy cannot find the true self. One who is always limpid cannot live. Instead, the goal of a balanced life is to be always renewable, because polarization results in illness.

Mary, Bert and the children visit her Uncle Albert who is sick. They find him floating on the ceiling, unable to come down, because he can’t stop laughing. The laughter lightens him against the pull of gravity. When he tells a funny joke, the children laugh and float up to join him. The only way to get down is to think of something sad. Mary Poppins announces “It’s time to go home”. Jane says “That’s the saddest thing I’ve ever heard”, and everyone descends. Mary Poppins and the children leave. Uncle Albert descends too, but now is stuck on the floor crying. He is so sad that he cannot get up. Bert remains to console him.

Uncle Albert suffers from polarization, always too happy or too sad, always floating away on glee or anchored to the ground by depression. In traditional Chinese medicine (another Taoist art), sickness results from an imbalance of yin and yang energies in the body. The cure is to re-balance the energies in the body. Wherever there is an imbalance within Tao (as there is at 17 Cherry Tree Lane, for example), energies flow in and restore balance. The resetting of an imbalance is called the Principle of Equalization, defined in the TaoTeChing ch. 77.

- Is not the way of heaven like the stretching of a bow?

The high it presses down,

The low it lifts up;

The excessive it takes from,

The deficient it gives to.

- TTC ch. 77; Lau, Tao Te Ching, p. 80.

Mary, Bert and the children regain their mobility by harmonizing joy with sadness. Uncle Albert’s extreme emotions overwhelm him. One minute he is bouncing off the ceiling because he possesses too much yang. The next minute he is back on Earth, but then he’s held down by the weight of too much yin.

G. DIRECTED SYNCHRONICITY AT THE FIDUCIARY BANK

In a reprise of the song “The Life I Lead”, Mr. Banks berates Mary Poppins for failing to discpline the children and for non-traditional activities that have not “molded the breed”. She reminds him that he really wants his children to follow his “straight and narrow path” and to celebrate the business of higher profits.

Although he is about to fire her, Mary Poppins “tricks” Mr. Banks into taking his children on an outing, to visit the bank where he works. As she puts the children to bed, she shows them a water globe with a model of St. Paul’s cathedral inside and sings “Feed The Birds”, about the bird woman, who sits on the steps of the cathedral, selling bread crumbs for others to show an act of kindness.

The song “Feed The Birds” and the visuals in that sequence seem to be a lesson in morality. It preaches charity for the “little birds” whose “young ones are hungry” and “their nests are so bare”. All it costs is tuppence to show that they care. That song is uncharacteristic of a Taoist sage, because classical Taoism rejects doctrinal morality. The TaoTeChing teaches that doctrinal morality is a sign that people have lost their way, that they have disconnected from their inborn nature and cannot sense the patterns in the world. Doctrinal morality is ritual, because it is based on cognition and principles, not inborn nature and Tao. Doctrinal morality appears when people have lost their sense of self.

- When the Tao is lost, there is goodness.

When goodness is lost, there is morality.

When morality is lost, there is ritual.

- TTC ch. 28; Mitchell, Stephen, Tao Te Ching, London: Pan Macmillan, c. 1989.

The true purpose of the song is to set up a run on the Bank of England and to get Mr. Banks fired to put them both back on course. During the job interview, Mary Poppins asks Mr. Banks, “Are you ill?” She acts like a physician and interacts with him as a patient, recapping the pattern of illness that has beset Cherry Tree Lane and that has diverted Tao currents here. Spontaneity, wu-wei, these concepts suggest free will and an unwritten future. Yet, there is evidence too of pre-destination. Mr. Banks runs his home “precisely on schedule”, but Mary Poppins “won’t have schedule interruptions” either. Her schedule supersedes his schedule. The pattern of illness and disharmony at 17 Cherry Tree Lane has diverted Tao currents there for treatment. (See also Internal And External Patterns In Medicine.)

The song “Feed The Birds” can be understood from a classical Taoist point of view as a song of introduction. The instruction in charity is what the Bird Woman says, her modus operandi, her methodology. The children are introduced to the Bird Woman, a catalyst in the scheme of things, in a vivid dream. The classical scriptures teach the importance of dreaming (daydreaming and sleep dreaming) for spiritual edification. The lullaby places the children in a meditative state (see ChuangTzu ch. 2, Watson, p. 87: they “cast aside ears and eyes” and “wander free and easy in the service of inaction”) and connects them to Tao:

- There are normal dreams, and dreams due to alarm, thinking, memory, rejoicing, fear. These six happen when the spirit connects with something. Those who do not recognise where the changes excited in them come from are perplexed about the reason when an event arrives…. When a body’s energies fill and empty, diminish and grow, they always communicate with heaven and earth, responding to the different classes of things.

- LiehTzu ch. 3; Graham, The Book Of Lieh Tzu, p. 66.

The story of Mary Poppins the movie is a look behind the scenes, a peek into the mysterious mechanisms at work in the universe. A Taoist universe is one of coincidences and synchronicities. Things happen seemingly without effort or planning (wu-wei). Mary Poppins hardly sees Mr. Banks again in the drama; and yet somehow George Banks and by extension the Bank of Englend, the two patients, will be healed. From the Book Of Chuang Tzu, “You have only to rest in inaction and things will transform themselves.” (ChuangTzu ch. 11, Watson, p. 122.)

H. THE TRIP TO SEE THE GATEWAY OF CREATION OVER THE ROOFTOPS OF LONDON

In the Book of Lieh Tzu, King Mou receives a powerful magician at the court and to persuade him to stay, builds the magician a magnificent mansion that costs almost the entire treasury. It comes with beautiful concubines, the best food and the finest clothes. In return, the magician takes King Mou on a trip in his dreams to a dazzling city in the clouds, made of silver and gold, jade and pearls with the most indulgent of pleasures. After 30 years, the magician sent the King back to his palace and told him it was all a dream, a journey of the spirit. It was a lesson that what is illusory and what is real cannot always be distinguished in the mind.

- “Your Majesty feels at home with the permanent, is suspicious of the sudden and temporary. But can one always measure how far and how fast a scene may alter and turn into something else?”

- LiehTzu ch. 3; Graham, The Book Of Lieh Tzu, p. 63.

The result of that lesson though was that the king gave up his responsibilities. “The King was delighted, ceased to care for state affairs, took no pleasure in his ministers and concubines, and gave up his thoughts to far journeys.” (LiehTzu ch. 3; Graham, p. 63.) In classical Taoism, things are in perpetual transformation, but some things like heaven and earth endure. (TTC ch. 7.) With cultivation and care, people can endure as well. (TTC ch. 22.) Although some things may be impermanent, they may disappear but then reappear in the cycles of transformation. (TTC ch. 40.)

In the rooftop sequence, Mary Poppins leans to the side of the real, when she leads them to see the Gateway of Creation to witness cosmic transformation. Transformation (化 hua) encompasses all change from biological growth to the pushing up of mountains to the cycling of the seasons. From TaoTeChing and IChing (易經 or yijing) symbolism, the trip to watch the ordinary sunset is a mystical trip to see the Gateway of Creation at the border between the cosmic energy fields of Great Yin and Great Yang, formed at the beginning of time. (TTC ch. 42.) Things gain their existence and achieve form in this matrix of Creation and enter the universe through the Gateway. (TTC ch. 5.) The symbols for Great Yin and Great Yang are moon and sun or heaven and earth. The Chinese character for change (易 yi) represents a sunset: the symbol for sun on top and a crescent moon below it. Thus, the pictogram of a sunset suggests that interaction of yin and yang is the source of both creation and transformation.

Bert has become a chimney sweep and is preparing to clean the fireplace at the Banks home. He tells the children to see the fireplace as a doorway to a world of enchantment. Michael grabs the brush from Bert to feel the pull of the wind in the chimney and is sucked up the chimney. Jane sticks her head in, calls out to her brother and is sucked up too. Mary and Bert join them on the rooftop and they explore the rooftops of London. They climb a stairway of smoke to the top of a steeple to watch the sun set.

From the song “Chim Chim Cheree”, there are echoes of yin-yang symbolism. The Gateway of Creation between Great Yin and Great Yang is like the place “‘Tween pavement and stars” or Heaven and Earth. All things in a Taoist universe are made of energy, a balance of the polar forces of yin (female principle) and yang (male principle). The interaction between them resembles the give and take of reproductive intercourse. When two fields of energy interact, they are like “smoke all billowed and curled”. The Gateway between Heaven and Earth is bathed in twilight like the rooftops of London where “there’s hardly no day Nor hardly no night”. In the nursery sequence, Mary Poppins’ empty carpet bag, from which she pulls all sorts of oversized objects, is a miniature Gateway of Creation. The bottomless fecundity of that empty carpet bag fits the verse: “Pump it and more and more comes out.”

- The space between heaven and Earth –

Isn’t it just like a bellows!

Even though empty, it is not vacuous.

Pump it and more and more comes out.

- Ames, Roger and Hall, David, Dao De Jing – A Philosophical Translation, New York: Ballantine Books, c. 2003, p. 84.

- Up where the smoke is all billowed and curled

‘Tween pavement and stars

Is the chimney sweep world

When there’s hardly no day

Nor hardly no night

There’s things half in shadow

And halfway in light

On the rooftops of London

Coo, what a sight.

The yin-yang emblem, called the tai-ji-tu (太極圖), is a symbol of Taoist philosophy, religion, divination, cosmology and metaphysics. In all those categories, certain characteristics and attributes of yin-yang are accepted truth. Thus, the symbol embodies the important principles of reality: the physical laws and philosophical and theological truths of the universe.

- 1. opposites/contradiction: the black and white swirls represent opposite forces in balance.

2. interdependence: Each force relies on the other

3. mutual inclusion: each force contains a seed of the other

4. interaction and resonance: yang stimulates and yin responds

5. complementariness: each force enhances the other

6. change and transformation. the two forces undergo transformation.

- Wang, Robin, Yinyang: The Way of Heaven and Earth in Chinese Thought and Culture, Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, c. 2012, pp. 8-13.

Mary Poppins has its own yin-yang symbol: the tuppence from Mr. Banks’ “Termination of Employment” segment. The coins shown slightly overlapping each other, in the obverse and reverse. The obverse and reverse sides recall the fields of yang and yin. Positioned like the union of two sets in a Venn diagram, the overlapping area suggests the interaction of the two forces. Although yin can transform into yang and vice versa, the two sides of a coin are stand for opposite energies, separate yet indivisible. Similarly, coins used in IChing divination represent yin and yang.

In the scene below, Mr. Banks has been fired from his job at the bank. The board of directors ask if he has any last words. Looking dejected and lost and overwhelmingly humiliated before his former colleagues, he reaches into his pocket and finds the tuppence, a gift from his children. The tuppence are a reminder of the importance of balancing emotions. Then acting as though to restore his equanimity, he bursts out laughing and shouts “supercalifragilisticexpialidocious” as he runs out of the room.

Because the bank is a “natural” institution (literally, a part of nature), Mr. Banks is not truly rejecting authority, as would a character like Bert or Mary Poppins. Rather, the termination is the beginning of transformation. He is re-born, like a butterfly, with wings – the children’s kite now repaired. The rest of the family is re-born with him and together they go out and fly the kite. At the end of the story, the two families merge into one extended family, when Mr. Banks is given a partnership at the Bank. The family name Banks now joins institutional family (Dawes) with the destined family (Banks) to set a new course for the world – because wherever the Bank of England goes, the rest of the world must follow (in the Edwardian view).

I. MARY POPPINS FOLLOWS TAO AND LEAVES WITHOUT SAYING GOODBYE

- To follow the Way is called completion. To see that external things do not blunt the will is called perfection… Such a man will leave the gold hidden in the mountains, the pearls hidden in the depths. He will see no profit in money and goods, no enticement in eminence and wealth, no joy in long life, no grief in early death, no honor in affluence, no shame in poverty…. His glory is enlightenment, [for he knows that] the ten thousand things belong to one storehouse, that life and death share the same body.

- ChuangTzu ch. 12; Watson, The Complete Works Of Chuang Tzu, p. 127.

In the last sequence of the movie (“Let’s Go Fly A Kite”), the wind that carried Mary Poppins to 17 Cherry Tree Lane has changed direction. The wind is analogous to chi currents, and they are telling her that it’s time to leave. As she packs, the children tearfully beg her to stay. “Don’t you love us?” they ask. When the entire family goes out to the park to fly a kite, forgetting about Mary Poppins entirely, the parrot head on her umbrella speaks to her and reminds her that they’ve forgotten her. “Don’t you care?” She replies “Practically perfect people never allow sentiment to muddle their thinking.” Then she opens her umbrella, lifts it to the wind and is carried away.

Empathy does not interfere with clear thinking in the sage. Earlier in the story, she tells the children “I shall stay until the wind changes.” A Taoist follows Tao and does not attach to externalities, because all things belong to a single storehouse, the Tao. Then in leaving, there is no real loss.

Mary Poppins really is unmatched as a classical Taoist primer. I’ve discussed only a few key scenes, but the entire movie could serve as an entree into a classical Taoist universe. Disney has released the movie on home video in several formats and editions since 1997. They restored the picture and sound for the 2004 40th Anniversary Edition on DVD.